Great Western Product Line

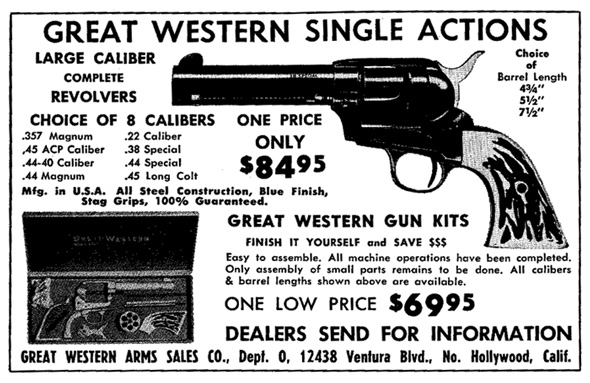

The flagship of the Great Western line, the Standard Model, was a fixed-sight SAA copy available in 43/4- , 51/2- and 71/2-inch barrels. Chamberings were advertised as .22 Long Rifle, .22 WMR, .38 Special, .44 Special, .357 Magnum, .38-40, .44-40, .44 Magnum, .45 ACP, .45 Colt, and “.357 Atomic.” The Atomic was a nonfactory .357 Magnum load incorporating standard brass, 16 grains of Hercules 2400 and a 158-grain bullet. Some claimed the .357 Atomic churned up 1,600 feet per second at the muzzle, which would have made it a real scorcher for its day. (For today, too.) Apparently, 50 or so Great Westerns were chambered for .22 Hornet, which was something unique: the first factory revolver to be chambered for a high-velocity varmint cartridge. According to Keith, some Standard Models were also chambered in .30 Carbine, another first, if true.

Some of those chamberings probably existed only in Great Western catalogs, as no production examples have been identified. As was true with many small gunmakers, there was apparently a reality gap between what Great Western’s catalog stated and what it built. No company production records remain, but Deubell, with whom Great Western is something of a passion, estimated that 50 percent of the company’s production was chambered for .22 rimfire.

A Buntline version with a 12- or 121/2-inch barrel was offered, as was a 31/2-inch-barreled Sheriff’s model that lacked an ejector rod assembly. A target version, the Deputy, featured a 4-inch barrel, a target front sight, an adjustable rear sight, and a full-length rib similar to the old King target rib popular in the ’30s and ’40s. A Fast Draw model with tuned action, brass grip frame and short front sight completed the revolver lineup.

Great Western also manufactured about 20,000 clones of the Remington Model III double derringer chambered in .38 S&W and .38 Special. The indefatigable Hunter simultaneously imported a West German double derringer that looked much like the Great Western, which further reinforced the impression that Great Western guns were shoddy postwar imports.

Actually, Great Western guns were built to take some punishment. The Standard or Frontier Model, for example, used the finest materials. The frame was forged steel. The hammer was made from 6150 chrome-vanadium steel. The hand, trigger and cylinder bolt were made of beryllium copper, and cylinders in calibers .357 and larger were made of 4140 chrome moly steel. That’s a lot of beef.

Actually, Great Western guns were built to take some punishment. The Standard or Frontier Model, for example, used the finest materials. The frame was forged steel. The hammer was made from 6150 chrome-vanadium steel. The hand, trigger and cylinder bolt were made of beryllium copper, and cylinders in calibers .357 and larger were made of 4140 chrome moly steel. That’s a lot of beef.

Finishes? Name it. You could have a Great Western in plain white metal; blued steel with case hardening; or Parkerizing, nickel plating, silver plating or gold plating, with or without engraving. If the faux-stag “Pointer Pup” grips didn’t thrill you, maybe ivory or mother-of-pearl would. For a buyer who wanted to save $20, Great Westerns were available in kit form — in white — for all calibers except .44 Magnum. Henry M. Stebbins said in Pistols: A Modern Encyclopedia, published by Stackpole in 1961, that the kits weren’t aimed at average shlubs.

“(These kits) aren’t for amateurs,” he wrote. “The machine operations are done, and instructions come with the kit, but the deburring, fitting, polishing and finishing are for the buyer to do or to have done. This calls for gunsmithing skill.” Kit guns were marked with a “0” serial prefix.

Fans and Detractors

Great Western peaked during its first few years. In a masterpiece of marketing straight from the pages of Col. Sam Colt, Wilson presented President Dwight Eisenhower with a beautiful Great Western. Wayne was given a pair of engraved, gold-trimmed, ivory-stocked Frontier Models. (He carried those in The Shootist.) California Gov. Goodwin J. Knight was given an inscribed presentation revolver, a gun now in Deubell’s collection.

Dee Woolem, a stuntman at Knott’s Berry Farm in California, went to bat for Great Western after perfecting a quick-draw technique that earned him the title of “father of fast-draw.” Woolem traveled the country, promoting himself and his new gun. Those celebrity tie-ins provided a promising start for Great Western, but all was not well.

It is not recorded that Wilson had a detailed understanding of the labor-intensive nature of firearms production. His company obviously lacked Colt’s 120-plus years of handgun-building experience. There is no question that Great Western used the finest materials, but its regular production guns were too often characterized by abysmal fit and finish. Word about that soon spread, aided by Keith, America’s most prominent handgunner.

In one of the most damning firearms reviews ever printed, Keith hammered Great Western in his popular 1955 book Sixguns, published by Bonanza Books.

“The (Great Western) gun we tested was very poorly timed, fitted, and showed a total lack of inspection,” he wrote. “The hand was a trifle short, the bolt spring did not have enough bend to lock the bolt with any certainty, the main spring was twice as strong as necessary and the trigger pull about three times as heavy as needed. … As received, it certainly was neither safe, nor in shape to have been put on the market.

“There is no earthly reason why this new single action could not be just as good as the famous old Colt, but it will have to have a lot of redesign work to ever make it superior. … I cannot recommend them as finished arms.”

Keith’s blistering review constituted Strike One for Great Western.

Strike Two was Ruger’s introduction of its Blackhawk single-action in 1955. The magnificent revolver had an indisputable “cowboy” look despite its adjustable rear sight and tall ramp front sight. Unlike the old Colt and Great Western, it was a “modern” single-action that featured coil, not flat, springs and an investment-cast frame that shaved cost without sacrificing strength. And, wonder of wonders, the Ruger Blackhawk retailed for about $87.50, which was $4 less than the Great Western Frontier at $91.50.

Strike Three was Colt’s crushing 1956 announcement that, on second thought, it would bring back the SAA. Faced with a creeping tide of red ink because of the cancellation of its Korean War contracts, Colt reversed its earlier decision, called the old SAA in from the bench and marketed it energetically. The high-quality Colt was everything the Great Western was — and everything it wasn’t, too. The new second-generation Colt retailed at $125, or 37 percent higher than Great Western’s comparable model. Price, however, was no object: Colt’s renowned quality and the genuine romance of the magic Colt name easily trumped the contrived romance of the Great Western.

Ruger and Colt splashed their new sixguns throughout the firearms media, advertising in prestige publications such as American Rifleman, where their full-page ads appeared regularly. The inevitable effect was that Great Western got lost in the noise generated by Ruger and Colt.